Snow changes things. Grass, for many weeks a sodden mire, is now fleece topped, with just a few mud patches visible. Gravestones and idle automobiles and inert things made of colder stuff have acquired a more impressive wintry cap.

Things, finally, look just as they should on these shortest days of the year, when the noontime sun blazes no warmer than the moon.

On the old public square, the Congregational church heaves a snow-dusted spire of dull green patina toward a bright December sky. Across the Christmas tree-studded median, in the white marble-framed picture window of the public library, St. Nick waves incessantly to quiescent Victorian carolers.

In the parking lot of the former Sparkle Market on the old Indian portage trail, a few brittle Christmas trees linger, forlorn, under strings of bare incandescent bulbs.

Over on Church Square, the giant hackberry tree has shed all of its leaves.

In the Methodist church, handbells and carols and ethereal melodies from a loaner Steinway piano, shrouded in Poinsettias presented in honor of the birth of Christ, waft out the wooden doors and into the city beyond. Mingling with the aroma of Schwebel's bread baking, these are the sights and sounds and fragrances of December, in my old hometown.

These could be the sights and sounds of any hometown in the temperate Eastern United States, perhaps in New England or anywhere across the Alleghenies where transplanted Yankees built Greek Revival churches on village greens over which elm trees would eventually tower, and then fall.

But there is something different here, hidden, unless you know where to find it:

Below the Vaughn Mansion.

Across from the fire station.

Behind the Sheraton Hotel where a great water powered mill once churned industrial turbines.

Underneath concrete pilings supporting the ceaseless whir of interstate traffic.

Shrouded by scrub brush and Ailanthus trees, here, our hidden river carves its knurly course, imperceptibly deeper.

Our Main Street was called Front Street, because it fronted this vital watery course, although by the time of my childhood, you'd be hard pressed to know it, as automobile dealerships, tool and die shops, a bowling alley, and cocktail lounges fronted this tawdry avenue.

Even still, there was the stub of an old bridge, called the Prospect Street bridge, which jutted out over where the river began its rapid descent and dramatic curve north, and on winter days we would trundle over to go look at icicles: such a simple winter pleasure.

Last winter our town kicked off a year-long Bicentennial celebration, with a Winter Festival downtown. There was ice skating on a refrigerated rink. Ice carving contests. The ceremonial tapping of a specially brewed Bicentennial Ale.

All is festive and bright, but on a whim, I decide to walk a block south, to see if the icicles are still there.

While hundreds revel within earshot, mine are the only footsteps on the wooden boardwalk that descends below the tree line, down a sandstone chasm the old timers called "The Glens."

Descending deeper, the drone of traffic disappears, until all you hear is the crooked river dancing briskly on its bed of smooth gray shale.

Gazing up, walls of Sharon Conglomerate sandstone, studded with quartz pebbles, range in color from gray to tawny to gold to black. And everywhere that water drips, at every crevice and pore, a magnificent crystalline spear, the perfect inversion of the Congregational church's spire, points not toward the crevice of blue sky above, but toward sparkling brisk waters below.

This unusually bright winter afternoon is almost over, and rays of the expiring sun illumine the icicles of the Eastern gorge wall. I pause to admire the illumination of icicles subtly colored by minerals seeping through from some deep source.

I look ahead to where the river turns course and disappears, at a point where a huge boulder, covered in Canadian hemlock and mosses and ferns that should only grow in more northerly climes, marks the transition of the Cuyahoga from south flowing river to one that runs north.

And suddenly this winter idyll is interrupted, as one icicle after another crashes dramatically into swift flowing water: just as the winter sun is about to set, it has warmed the icicles to their perfect breaking point.

On this winter afternoon, I am so grateful to know this secret place where the river bends, so thankful to have been bundled up for those childhood sojourns where we went seeking majestic places in our own backyard.

Decades later, I learn that in Victorian times excursion trains brought thousands each day to these very Highbridge Glens, where they descended picturesque staircases to reach a riverside promenade, crossed gurgling rapids on swinging bridges, and sought out caverns and grottoes to which they gave fantastical names.

In the winter, they called these very cavern walls, just a few blocks from my parents house, the Crystal Palace.

This quirky, hidden river is the living soul of my old hometown, the reason people settled in these unlikely parts.

The simple pleasure of walking out on a bridge, to look at icicles, is one of many simple winter pleasures that I fondly recall on these darkest days of the year, whenever the first snow falls:

Being bundled up in more layers than seems possible, feet encased in three pairs of socks, bread bags, and rubber galoshes, to be pulled by Dad on a sled down the middle of Seventh Street. Tim falls backward, so immobilized by snow pants and parka, that he is a helpless turtle on his back.

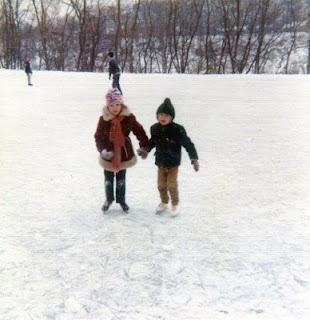

Donning double-bladed skates to ice skate clumsily on chunky ice at the Gorge, where water was impounded to flood a field in a Depression-era ice rink, and the best part was singing damp mittens on the rusty iron warming stove.

Epic December journeys to Lancaster, Ohio, the Plymouth Volare station wagon scented with Thermos-warmed coffee, and a highlight was stopping at an old country store at the junction of state route 23, to see the purported last black bear of the Ohio frontier, living out his desolate golden years in an odoriferous cage.

Decorating the Christmas tree to tunes from old scratchy records spinning carols, on Mom's maple cabinet stereo, no homemade ornament to homely to earn a place on the tree.

Dad pulling a volume of the Best Loved Poems of the American People from the overflowing bookshelves, and we sat, enthralled, as just his words and flawless narration brought the saga of Casey, and the despair of the denizens of Mudville, to vivid life.

These winter memories are the crooked knurly river of my memory. They are always there, like our silent hidden river, and I am so fortunate to be able to call them up, to have them enliven every Christmas season and remind me of simple pleasures which form the craggy sandstone bedrock of who I am.

We sought out the icicles.

We skated on rutted ice.

We made a sledding hill out of an almost imperceptible backyard slope.

These memories and experiences are the Crystal Palaces, the great treasures that so many people seek, in all the wrong places, because they don't know that the most amazing things are often the simplest ones, and that sometimes it takes a welcome cloak of muffling snow, to blot out unnecessary distractions, and to inspire the introspection that these darkest days of the year require, in order to to find the hidden river, and the crystal palaces, that were right there all along.