The River Finds Its Way

Each day the sun rises, and the sun also sets. But no two days are ever the same. Here, we muse about the urban landscape, things that grow, and the way the moon hovers on this night. Because no day will ever be just like this one again.

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

The River Will Find Its Way

Tuesday, January 28, 2014

Meeting Pete Seeger

|

| Me, far right, in the Gulf at Galveston, on the road to the Kerrville Folk Festival, sometime in the 90s. |

News of Pete Seeger’s death flowed from my car radio this frigid January morn, and I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had met him.

Sunday, August 4, 2013

The River Finds its Way

Thursday, March 21, 2013

The Persistence of Geese

Suddenly, in a day, everything has changed amongst the birds.

Winter was a time to hunker down.

Enormous flocks of Canada geese wintered with us, slumbering en masse at night on the iced lake, by day grubbing voraciously through a mantle of snow to pluck victuals from the turf. In their wake, a cacophony of churned earth and webbed foot prints.

Of a January vineyard morning, I would crunch through diamond-crusted snow before sunrise.

Coming to a small patch of open water, and the flotilla of ice where our swans slumber, I feel like I've entered a secret avian dream world: All is peace and crystalline beauty.

The swans allow a small trusted bevy of geese to sleep amongst them on their floating bed chamber, the rest banished to the lakeshore with the ducks. How very wise, I think, to have these squawky sentries close at hand during the vulnerable silent hours.

During these peaceful winter mornings, I observe that our ducks never sleep on the ice, except when there is a downy blanket of snow. On a snowy January morning, I arrive at sunrise to find our entire duck colony asleep on snowy ice. As the sun rises, they arise and begin chattering amongst themselves, waddling busily on the ice. (I think I could be content to watch ducks walk on ice all day.)

But change is afoot in the vineyard, the quickening of the year.

Skunk cabbage shoots rise steamily from the creekbed. Gliding raptors, aloft in a sky that is suddenly cerulean, dangle entrails of branches. On a rainy morning I notice our pair of mute swans display a newfound interest in golden willow branches that litter the lawn.

These quickening days: Behold! And turn your eyes to the March firmament:

To the South, golden rays, impossible blue skies, fluffy white clouds.

Northward, impending wintry nebula, dark and foreboding.

Snow flurries mix with drizzle and warmth.

This fleeting season, marked by the mysterious arrival of impossibly vivid ducks, with crimson necks.

Raw, windswept March, when you experience all of the seasons in just one day. The mysterious crimson ducks flit about on a choppy windswept lake for a just a few days, then disappear as quickly as the whiteout flurries that materialize to displace a mid-afternoon sliver of golden sun and clear blue sky.

The day of the crimson ducks marked a noticable change in avian behavior.

All winter everyone got along, but today our territorial male swan was bound and determined to keep a pair of Canada geese from nesting under a cherry tree. I could swear they are the exact same pair that nested here last year, under a dead pine tree. I christened them Irmgard and Heinrich, in homage to a certain Germanic persistence they seemed to possess.

As the days lengthen, gone are the large colonies of ducks who gobbled at the swan chow bowl on frigid winter days.

Gone the riotous gaggle of geese who slumbered on the ice by night and rooted riotously through vineyard rows for daytime grub.

Gone the marauding robins who came out of nowhere to strip to bare twigs a crabapple tree which had somehow held its fruit through Christmas.

On these transitory lion/lamb March days, the birds have all paired off:

The swans daub a nest from mud and leaves and willow branches in a swampy finger of the lake.

An iridescent mallard and his handsome brown speckled bride toddle about the shrubbery at sunrise, looking for a place where in a few weeks she may deposit her eggs.

A pair of elegant mourning doves coo beside a decaying old grape press in the rose bushes, seemingly grateful for the now bare earth on which to roost.

There is something to be said for a day tending a vineyard.

Even if it is a day that starts with pelting sleet and a glaze of ice. Especially if it is a day during that magic month when the year quickens perceptibly, and avian behavior takes a marked seasonal turn. An entire complex avian world goes about its seasons on the shore of this lake, and I feel privileged to be here to watch it unfold.

Throughout it all, in every season, a solitary Great Blue Heron swoops overhead, knowingly.

And I kind of get the feeling the heron is orchestrating the whole thing.

But as exciting as it is, to perceive each day advance into a new season, and sense a new warmth, and a hopeful stirring amongst the paired off water fowl, I find myself missing just a little bit those solitary winter days, and magic sunrise mornings, when an ever-changing cast of migratory waterfowl bedded down peaceably on a pallet of ice.

And I can't get past the persistence of these geese, this single pair who have staked their claim in hostile terrain.

Last year they built a nest under a dead pine tree. A tree crew felled the pine carcass, and ground it to mulch.

But Irmgard and Heinrich were back the next day, building a new nest atop the wood chips.

This year, after the rest of the wintering Canadian horde has departed, they have their sights on a gnarled old cherry tree. The grub around its exposed roots, roost in various positions at the base of its woodpecker-dimpled trunk, taste a few shriveled cherries that have fallen to the grass. (They seem to be practically measuring the place for draperies.)

Periodically, our resident male swan takes a break from nest building, and chases the geese off the water, with impossibly powerful strokes of his enormous webbed feet.

He overtakes them near the shore, and they retreat to the cherry tree.

The swan hurumphs himself out of the water, and charges toward them with his ungainly, but still frightening (and surprisingly speedy) gait. Geese and swan charge through pine bowers and vineyard rows, but the geese are fleet on land, and the swan seems to know his strengths, so he never advances too far from the lake.

This goes on for hours, a pursuit by water, by air, and by land.

These placid geese seem mostly nonplussed, and the swan seems to realize he is mostly just making a point.

Eventually the geese will lay three or four large ovoid eggs in a nest of pine needles and down, at the base of the cherry tree. The swan will continue his aggression, ceasing sometime in June when his own mate is off her twiggy willow throne, and order will be restored to the peaceable avian kingdom.

Then the geese will sun themselves with the swans on the grassy lake shore on languid summer afternoons, the ducks hunkered and chortling amongst them, as they await the arrival of the winter hordes, and perhaps gossip just a little, about the mysterious crimson ducks, who came for just a few fleeting March days.

Tuesday, December 25, 2012

Crystal Palaces

Snow changes things. Grass, for many weeks a sodden mire, is now fleece topped, with just a few mud patches visible. Gravestones and idle automobiles and inert things made of colder stuff have acquired a more impressive wintry cap.

Things, finally, look just as they should on these shortest days of the year, when the noontime sun blazes no warmer than the moon.

On the old public square, the Congregational church heaves a snow-dusted spire of dull green patina toward a bright December sky. Across the Christmas tree-studded median, in the white marble-framed picture window of the public library, St. Nick waves incessantly to quiescent Victorian carolers.

In the parking lot of the former Sparkle Market on the old Indian portage trail, a few brittle Christmas trees linger, forlorn, under strings of bare incandescent bulbs.

Over on Church Square, the giant hackberry tree has shed all of its leaves.

In the Methodist church, handbells and carols and ethereal melodies from a loaner Steinway piano, shrouded in Poinsettias presented in honor of the birth of Christ, waft out the wooden doors and into the city beyond. Mingling with the aroma of Schwebel's bread baking, these are the sights and sounds and fragrances of December, in my old hometown.

These could be the sights and sounds of any hometown in the temperate Eastern United States, perhaps in New England or anywhere across the Alleghenies where transplanted Yankees built Greek Revival churches on village greens over which elm trees would eventually tower, and then fall.

But there is something different here, hidden, unless you know where to find it:

Below the Vaughn Mansion.

Across from the fire station.

Behind the Sheraton Hotel where a great water powered mill once churned industrial turbines.

Underneath concrete pilings supporting the ceaseless whir of interstate traffic.

Shrouded by scrub brush and Ailanthus trees, here, our hidden river carves its knurly course, imperceptibly deeper.

Our Main Street was called Front Street, because it fronted this vital watery course, although by the time of my childhood, you'd be hard pressed to know it, as automobile dealerships, tool and die shops, a bowling alley, and cocktail lounges fronted this tawdry avenue.

Even still, there was the stub of an old bridge, called the Prospect Street bridge, which jutted out over where the river began its rapid descent and dramatic curve north, and on winter days we would trundle over to go look at icicles: such a simple winter pleasure.

Last winter our town kicked off a year-long Bicentennial celebration, with a Winter Festival downtown. There was ice skating on a refrigerated rink. Ice carving contests. The ceremonial tapping of a specially brewed Bicentennial Ale.

All is festive and bright, but on a whim, I decide to walk a block south, to see if the icicles are still there.

While hundreds revel within earshot, mine are the only footsteps on the wooden boardwalk that descends below the tree line, down a sandstone chasm the old timers called "The Glens."

Descending deeper, the drone of traffic disappears, until all you hear is the crooked river dancing briskly on its bed of smooth gray shale.

Gazing up, walls of Sharon Conglomerate sandstone, studded with quartz pebbles, range in color from gray to tawny to gold to black. And everywhere that water drips, at every crevice and pore, a magnificent crystalline spear, the perfect inversion of the Congregational church's spire, points not toward the crevice of blue sky above, but toward sparkling brisk waters below.

This unusually bright winter afternoon is almost over, and rays of the expiring sun illumine the icicles of the Eastern gorge wall. I pause to admire the illumination of icicles subtly colored by minerals seeping through from some deep source.

I look ahead to where the river turns course and disappears, at a point where a huge boulder, covered in Canadian hemlock and mosses and ferns that should only grow in more northerly climes, marks the transition of the Cuyahoga from south flowing river to one that runs north.

And suddenly this winter idyll is interrupted, as one icicle after another crashes dramatically into swift flowing water: just as the winter sun is about to set, it has warmed the icicles to their perfect breaking point.

On this winter afternoon, I am so grateful to know this secret place where the river bends, so thankful to have been bundled up for those childhood sojourns where we went seeking majestic places in our own backyard.

Decades later, I learn that in Victorian times excursion trains brought thousands each day to these very Highbridge Glens, where they descended picturesque staircases to reach a riverside promenade, crossed gurgling rapids on swinging bridges, and sought out caverns and grottoes to which they gave fantastical names.

In the winter, they called these very cavern walls, just a few blocks from my parents house, the Crystal Palace.

This quirky, hidden river is the living soul of my old hometown, the reason people settled in these unlikely parts.

The simple pleasure of walking out on a bridge, to look at icicles, is one of many simple winter pleasures that I fondly recall on these darkest days of the year, whenever the first snow falls:

Being bundled up in more layers than seems possible, feet encased in three pairs of socks, bread bags, and rubber galoshes, to be pulled by Dad on a sled down the middle of Seventh Street. Tim falls backward, so immobilized by snow pants and parka, that he is a helpless turtle on his back.

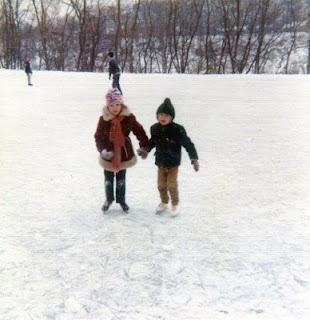

Donning double-bladed skates to ice skate clumsily on chunky ice at the Gorge, where water was impounded to flood a field in a Depression-era ice rink, and the best part was singing damp mittens on the rusty iron warming stove.

Epic December journeys to Lancaster, Ohio, the Plymouth Volare station wagon scented with Thermos-warmed coffee, and a highlight was stopping at an old country store at the junction of state route 23, to see the purported last black bear of the Ohio frontier, living out his desolate golden years in an odoriferous cage.

Decorating the Christmas tree to tunes from old scratchy records spinning carols, on Mom's maple cabinet stereo, no homemade ornament to homely to earn a place on the tree.

Dad pulling a volume of the Best Loved Poems of the American People from the overflowing bookshelves, and we sat, enthralled, as just his words and flawless narration brought the saga of Casey, and the despair of the denizens of Mudville, to vivid life.

These winter memories are the crooked knurly river of my memory. They are always there, like our silent hidden river, and I am so fortunate to be able to call them up, to have them enliven every Christmas season and remind me of simple pleasures which form the craggy sandstone bedrock of who I am.

We sought out the icicles.

We skated on rutted ice.

We made a sledding hill out of an almost imperceptible backyard slope.

These memories and experiences are the Crystal Palaces, the great treasures that so many people seek, in all the wrong places, because they don't know that the most amazing things are often the simplest ones, and that sometimes it takes a welcome cloak of muffling snow, to blot out unnecessary distractions, and to inspire the introspection that these darkest days of the year require, in order to to find the hidden river, and the crystal palaces, that were right there all along.

Monday, November 12, 2012

A Memory of Walnut Trees

Certain older people of my youth knew where the good trees were.

For my grandmother in Southern Ohio, the hickory trees halfway up the slope of Mt. Pleasant merited a journey. Clutching brown paper Kroger bags we debark from the brick path behind her house, down the alley, up a crumbling and slightly mysterious set of steps at the base of the mount.

Excited, we cross the threshold to a well-trodden wood. Lover-carved tree boles. Dirt bike ruts. Spongy mushrooms or jack-in-the pulpit or doll eye plants draw our eye. Somewhere off the spider grid of dusty trail, we pass an enormous grapevine swing, then a grove of ancient mountain laurel, and finally, the hickories.

Strewn on the slope there, what seemed like impossible riches. Vague memories of stout trees with wide canopies, perfectly formed. But below them, on the ground, the reason for our journey. We stuff the best ones, filling our Kroger bags and begin the journey down and homeward, heavy laden with hickory nuts.

Two my third grade eyes, my teacher had something of the aspect of an old country school marm, with an olive green upright piano in the corner of her classroom, upon which every morning she pounded out "My Country tis of Thee."

She'd then have us take out a single sheet of ruled theme paper, and fold it in two, three, or four columns, depending on the day's lesson. We were then to write ARITHMETIC ("A Rat In Tom's House Might Eat the Ice Cream") across the top, in our best block letters.

The first week of third grade, she led us out to a tiny swale in the front yard of our newish buff-colored brick school, and had us gather walnuts from a twin set of trees that grew there where the avenue swerved and then led down to the great falls at High Bridge Glen.

Dim memories of a certain reverie when she spoke of these trees, a certain hush and awe that she shared with other older relatives of mine, when they spoke of walnut trees. Impossibly slow growing. Incredible timber value. The strength, the exquisite grain of its heartwood.

Tales of old dingy furniture possessing magic beneath cracked layers of ill considered paint. Tales of widows swindled by unscrupulous lumbermen, felling ancient sentinel dooryard trees and offering but a fraction of their worth.

The gathering of walnuts on the schoolyard the first week of third grade was not part of any lesson plan that I recall. We weren't studying ecology, or native trees of Ohio, or botany. We simply gathered walnuts because Mrs. Reynolds knew that they were there, and wanted us to, as well.

For an old country woman, it wouldn't do for a thing of value and potential nourishment to moulder on the schoolhouse lawn, or be ground and flung by mower blade.She taught us that beneath their acrid tangy outer husks, an acid green with stiff quills of hair, you would find the sweet oily kernels. Ripping them open, we'd feel a tinge on our hands, pungent black sap mildly burning and staining our skin.

She warned us not to keep them too long in our brown paper sacks, they might rot and be eaten by worms.

This September, standing next to an old hedgerow, a walnut tree I had never noticed plunked her fruit to the ground. Suddenly, that bracing astringent aroma, and with it, a flush of schoolhouse memories.

As one acid green tennis ball after another fell to the ground, from branches decked in frond-like serrated leaves just beginning to turn gold, I was taken back to a time when I knew where the sweetgums stood, and the horse chestnuts, and the myriad oak trees with their various acorns.

All of these treasures dropping from the sky, there for the plucking, if you were lucky enough to know certain older people, who knew where the good trees stood.

Sunday, November 11, 2012

Elegy for a Swan

Of a September sunrise, banks of lespedeza thunbergii drip bowers of pink pea blossoms over still water. A pair of white mute swans and their brood of adopted ducklings slumber on the lake shore, head under wing.

Four great blue heron ring the shore, perched equidistant on spindly leg. The moment I arrive, they take off in simultaneous prehistoric flight, rising on teradactyl wing into the misty vapor burning off toward the sun.

September's fleeting perfection. These goldenrod days.

But as the poet observed, nothing gold can stay.

This first day of October, our big male mute swan glides the lake slowly, emitting a plaintive wail.

The old folklore has it that the mute swan, Cygnus olor is silent its entire life, until at death it emits just one exquisite song: the distilled essence of a placid regal life.

I know nothing of this folkloric final song, but the Cygnus olor I have come to know are not mute. This spring, for example, our female swan honked plaintively, mourning shattered eggs she lovingly tended on her floating twiggy throne.

This first day of October, it is Giuseppe, our fierce male, who glides the lake emitting the saddest possible song.

This weekend his lifelong mate Gina dipped her long graceful neck below water for the last time.

Her buoyant corpse greets us this first October morning. Her mate for life circles the lake mournfully. Together, as a pair, each ensuing season they hone their skill, ferociously guarding their territory, warding off predators, defending their eggs in tandem.

Now she rests on these old Canton acres. We buried her beneath an arborvitae tree.

It seems wrong, somehow, she, a creature of grace and of water, moored to this pebbly ground.

The old timers say, the sudden arrival of a wild swan on your lake brings incredible luck.

And so this spring began, on this very pond. A perfect crystal morning. A great swooping of white wings. And then, suddenly, placidly gliding on the water, a new young male swan, a feisty cob, in the center of the lake.

Displays of strength ensue, as our old male swan with a bum foot fends off a potential rival. His pen swimming prettily, weighing her options.

Onto the ground the rival cobs toddle, an awkward charge through vineyard rows.

And suddenly of a bright spring morning, the intruder swan is gone, as quickly as he arrived, as if a phantasm, as if a fever dream.

Their idyl restored, our resident pair glide the lake once more in tandem: circles, pirouettes, a mirror reflection of elegant necks joined as a heart.

The tender chivalry of these blinding white birds, he placing bits of scratch feed below water for her to gracefully retrieve. She so gentle in the tending of her nest, a regal throne on which she enshrined herself for many lean months, on brittle eggs that never hatch, reaching to scrape sustenance from those low branches her long neck could reach.

The mutability of the swan.

Good fortune and the arrival of luck in spring.

Death and lament in autumn.

I know nothing of the fabled swan song, the mythic melody that arrives only just before the moment of death.

But this I know, these swans are not mute.

Twice this year I heard swans cry.

She, in April, over shattered eggs she lovingly tended.

He, in October, in lament for his mate, probably weakened, tending her eggs far too long after they should have hatched.

And so autumn ends in Canton, after a perfect golden September, a perfect sunrise moment that of course cannot stay.